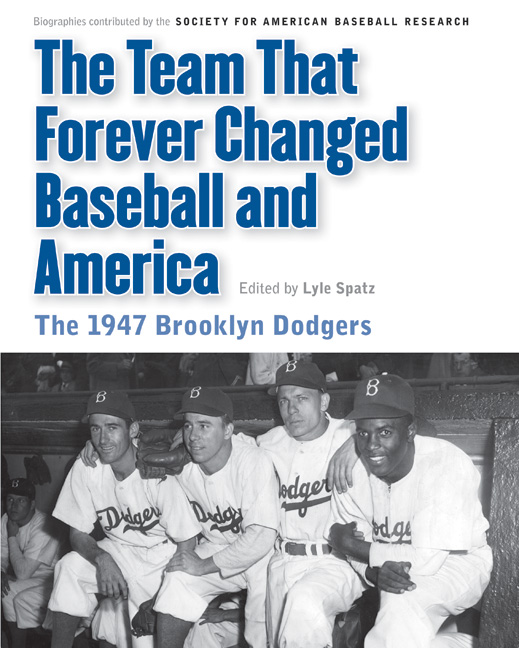

Integration (1947)

On the day Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier, it had been approximately 63 years since the last Black man, Moses Fleetwood Walker, had played in the majors. The Brooklyn Dodgers general manager, Branch Rickey, received the credit for bringing in Robinson, but the process of integration was ploddingly slow and carefully planned.

-

1939-1945

World War II led to the loss of good baseball players

By the time many of those players returned, they were no longer in their physical prime. Branch Rickey realized the necessity of planning baseball's future by looking towards the Negro Leagues. He framed integration as inevitable and profitable.30

-

November 25, 1944

MLB Commissioner, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, died

Landis, baseball's first commissioner, had long opposed any notions of integrating the league. His successor, Happy Chandler, was more open to the idea.33

-

March 12, 1945

NY passes the Ives-Quinn Act and the Fair Employment Practices Act

Banned discrimination in employment. This gave Branch Rickey the legal permission to recruit Black players.30

-

1945

Cleveland Buckeyes swept the Homestead Grays in the Negro League World Series

There was a notable lack of celebration for this accomplishment. Times were changing, and the Negro Leagues would soon be deemed a relic of Jim Crow.30

-

1945

Formation of the United States League (USL)

Created by Branch Rickey, this league served as a cover for him to scout the Black player that would eventually break the color line. Jackie Robinson never played here.34

-

October 23, 1945

Branch Rickey signed Jackie Robinson to the Montreal Royals

Robinson was carefully scouted to be the man to break the color line. He had to remain poised and dispassionate in the face of extreme racial animus. Rickey portrayed the Negro Leagues as a racketeer operation instead of a legitimate business to justify his refusal to pay the KC Monarchs for Robinson. This set the precedent of MLB teams stripping the Negro Leagues of their best players without proper compensation.30

-

1946

Branch Rickey signed 4 more Black players

He signed the following players:35

- Roy Campanella

- Don Newcombe

- John Wright

- Roy Partlow

-

1946

Jackie Robinson led the Montreal Royals to victory

He led the league with .349 batting average and 113 runs scored. The Montreal Royals won both the International League Championship & Junior World Series that year.30, 35

-

April 15, 1947

Jackie Robinson debuted for the Brooklyn Dodgers, breaking the color line after six decades

Approximately 26,000 fans bore witness to this event, about 14,000 of whom were Black. During his rookie year, he battled an incredible amount of racism from fans, opposing players, and even his own teammates. However, he proved to be worth the gamble that Rickey made, maintaining his dignity in the face of such prejudice and paving the way for future Black players.36

-

July 5, 1947

Cleveland Indians purchased the rights to Larry Doby from the Newark Eagles, making him the second Black player to integrate

Unlike Rickey, Cleveland owner, Bill Veeck, at least compensated the Eagles' owners, the Manleys, for Doby, albeit at far below his actual value.37

-

1947

Jackie Robinson won the inaugural Rookie of the Year Award

The 1947 Dodgers would lose to the NY Yankees in the World Series. This award would later be renamed in his honor. His 1947 statistics included36

- hit .297

- 29 stolen bases (led league)

- 125 runs scored (2nd in National League)

- 175 hits and 12 home runs in 151 games

- walked 74 times

- 16 errors at first base (2nd in league)

-

July 21, 1959

Boston Red Sox became the last team to integrate, signing Pumpsie Green

While certainly not the only team to resist integration until there was sufficient backlash, Boston was the last team to cross the line. Even after, it was still difficult for Black players to join major league teams, as many had implemented quotas.38